After reading everyone’s insightful posts and revisiting my notes on partnerships, I became curious about the PE business model and its inherent tensions with fairness and good faith in partnerships. While the broader debates around the PE industry are significant, this post focuses on its organizational structure and revenue model. Thanks for indulging my not-so-well-formulated question! 😸

Background:

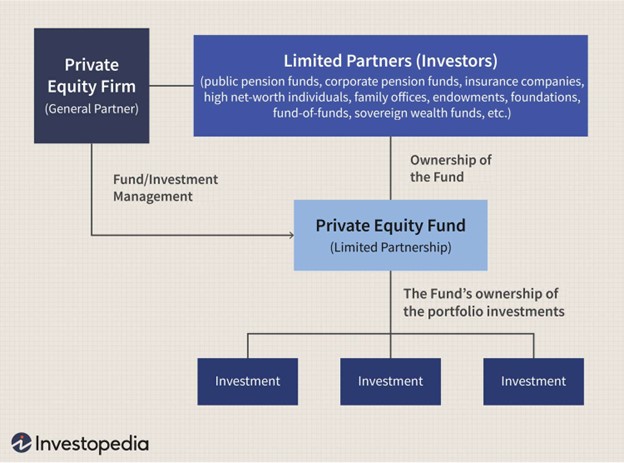

Private equity (PE) firms occupy a unique and often controversial role within the business ecosystem. These firms typically operate within a limited partnership structure, where general partners (GPs) manage the fund and make investment decisions, while limited partners (LPs), such as pension funds, endowments, and wealthy individuals, provide the capital. The funds raised are invested into portfolio companies, which are often underperforming or high-growth businesses that PE firms aim to restructure, grow, or profitably exit through a sale or public offering [5].

Proponents argue that PE drives growth and innovation by injecting capital and expertise into these businesses, revitalizing companies, and expanding the economic pie [4]. In some cases, PE firms invest in socially impactful ventures – green technologies, rural hospitals, and local manufacturing – channelling returns back to investors [4]. PE firms do, in fact, play an essential role in the tech and innovation ecosystem by providing liquidity for venture-backed startups. As noted by Valerie Mann, there is a scarcity of IPOs in the current market, particularly in Canada. PE acquisitions create necessary exit opportunities for investors and founders [4][5].

Now Back to Our Regularly Scheduled Programming…:

From a BC perspective, the practices of many PE firms appear antithetical to the principles in the British Columbia Partnership Act [1][2].

BC Partnership Act:

Fairness and Good Faith

Section 22(1):

A partner must act with the utmost fairness and good faith towards the other members of the firm in the business of the firm.

Accountability for Benefits

Section 32(1):

A partner must account to the firm for any benefit derived by the partner without the consent of the other partners from any transaction concerning the partnership or from any use by the partner of the partnership property, name, or business connection.

After understanding that good faith and accountability for benefits are statutorily mandated, I am confused by the practice of forcing management services agreements (MSAs) onto portfolio company management.

Sample MSA from an SEC Filing

These agreements force distressed portfolio companies to pay advisory and management fees to PE firms that place senior managers into acquired portfolio companies. While legally permissible, these fees often drain critical resources from companies that PE firms are supposed to help restructure and grow [2]. Such practices raise questions about whether PE firms truly adhere to partnership principles or are maximizing “personal” benefits at the expense of LPs:

- PE firms install “advisors” with minimal relevant expertise to oversee startups, siphoning cash from companies that bootstrapped their initial growth.

- Additionally, these firms continue to charge LPs their standard “2 and 20” fees: a 2% annual management fee on assets under management and 20% carried interest on profits.

For LPs, their return on investment depends on the successful turnaround of portfolio companies and receiving distributions based on the fund’s profitable investments (i.e., growth in valuations). For GPs, however, profits are derived through multiple streams: management fees and advisory fees charged to portfolio companies (MSAs) and carried interest on top. This creates a misalignment between the different “partners.”

Risk Mitigation Tools and Misalignment

The misalignment extends to tools like earnout provisions designed to mitigate acquisition risks. Earnout provisions allow buyers to defer part of the purchase price until specific performance metrics are met post-acquisition. While these provisions reward sellers for achieving projected revenues or milestones, they can disincentivize acquirers from actively managing portfolio companies. GPs may instead focus on clawing back purchase price holdbacks, collecting fees, and neglecting long-term company success [1].

Misalignment with BC Partnership Principles

The British Columbia Partnership Act emphasizes fairness, good faith, and equitable sharing of benefits among partners—values that starkly contrast to many PE practices. Extracting fees from distressed companies or enforcing distribution waterfalls that heavily favour GPs exemplifies a model that prioritizes financial engineering over partnership principles.

This post is certainly not a lament for wealthy LPs, and I assume that most partnership agreements fully disclose and allow for fee collections. However, founders and advisors should be aware of these practices to safeguard innovative products and services (and, as a general rule of hygiene, should avoid them).

After all, when the dust settles, it’s not just “rich people stealing from rich people” – it’s the startups, their employees, and the broader economy that stand to lose.