The Role of AI as a CEO

Hi Everyone, I hope this post is not too late to reach all of you, but I wanted to share this article that I came across regarding AI CEOs now that the exam season has just ended. It was intriguing to read about how Swedish company Klarna released a video of their CEO Sebastian Siemiatkowski […]

Corporations, Charities and Director’s Liability

A few weeks into our class, there was a brief discussion regarding the liability of directors of charity. If my recollection is correct, they are held to a different standard and are often not liable which had something to do with not wanting to impose liability on entities that purport to do good for our […]

Deny. Defend. Depose: A New Model of Corporate Accountability?

Deny. Defend. Depose: A New Model of Corporate Accountability? Here’s a spicy one to cap off the semester. For anyone who is still paying attention, here is my manifesto- err, rambling thoughts on why the people celebrating Brain Thompson’s murder are not entirely horrible or irrational. A very wise creative writing teacher once told me […]

Shareholders First, Ethics Later: The Duty of Ruthless Profit Maximization.

I should be studying for exams or writing papers, but I saw this on LinkedIn this morning and immediately thought of biz orgs: NEWS OF THE WEEK! I also want to point out that the Elon Musk Twitter (sorry, X*) post indicated in the screenshot is FAKE NEWS, a completely fabricated/doctored X post, but this Simon Potter […]

Nevada Probate Commissioner Rules Against Rupert Murdoch’s Change to Family Trust

Hi everyone! Since we’ve been following the Murdoch family saga/drama over the last few months, I thought I would post an update to the situation as the NY Times just came out with an article about it. As a quick recap, Rupert Murdoch, the founder of Fox Corporation (and Fox News — which is known […]

‘Effective’ Corporate Environmental Responsibility in China

It is known that China is one of the largest polluters in the world in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and other toxic substances. However, people in the West sometimes overlook how much China has improved in terms of its environmental initiatives in recent years. For instance, China’s air and pollution levels have actually been […]

UBC’s Secret Coke Deal

Howdy, hope y’all are hanging in there alright during crunch time and I wish you all the best with finals. Part of my executive duties with the LSS is to attend every AMS Council meeting this school year. Per tradition, each AMS Council meeting includes a fun fact segment about UBC. Recently, our Archivist and […]

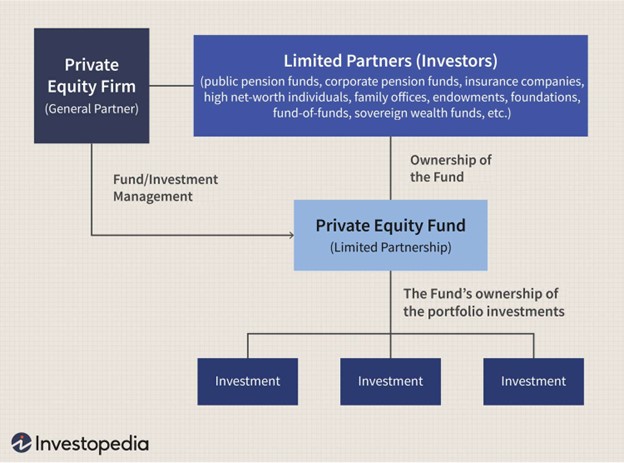

Private Equity: Where Fairness and Good Faith Go to Die (But the Fees Thrive)

After reading everyone’s insightful posts and revisiting my notes on partnerships, I became curious about the PE business model and its inherent tensions with fairness and good faith in partnerships. While the broader debates around the PE industry are significant, this post focuses on its organizational structure and revenue model. Thanks for indulging my not-so-well-formulated […]

CEOs on the Chopping Block – Stellanis CEO Forced Out | Shareholders sue Stellanis

For those unaware: Stellanis is a corporation formed from a merger of Fiat Chrysler and Peugot. They collectively control 14 well-known car brands, including Chrysler, Dodge, and Maserati. Stellanis CEO Carlos Tavares resigned this week on Sunday. He was Stellanis’ first CEO after its formation in 2021. The news comes as Stellanis and virtually every […]

The Hawk Tuah Meme Coin and the Perils of an Unregulated Market

Intro Nobody has posted about this yet, so I might as well. I suspect that this issue is more relevant to securities law, but it does have some relation to the core issues we examine in business organizations. Also, this is a developing story. I do not have the complete picture, and the issues and […]

Class 13 Slides & Video

Intel CEO “Retires” after Clashing with Board of Directors

Intel CEO “Retires” after Clashing with Board of Directors Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger “retired” a few days ago on December 1 after he had been appointed to the position just three years ago in 2021. The official Intel press release had stated Gelsinger retired on his own accord. Subsequently, news outlets, citing reliable insider sources, […]

On the UnitedHealthcare shooting…

If you’ve been following the news in the last few days, you may have heard about the fatal shooting of UnitedHealthcare’s CEO, Brian Thompson, on Wednesday. I first came across this news due to some tweets that were mocking the police’s efforts to find the shooter, among a clear lack of empathy for Thompson’s death. […]

Corporate Governance in AI Companies: Insights from the OpenAI Crisis

Corporate Governance in AI Companies: Insights from the OpenAI Crisis The corporate crisis that unfolded at OpenAI in November 2023 inspired me to reflect on corporate governance in AI companies. The crisis, which concluded with Sam Altman’s reinstatement and board restructuring, offers valuable insights worthy of discussion. While many analysts drew parallels to Steve Jobs’ […]

Now AI Washing? Is There Anything a Corporation Won’t Try?

I couldn’t resist posting this link to an article I found by Stewart Muglich, “AI Washing: Regulator Urges Accurate Disclosures by Issuers . At one point the article states, when “statements are not supported by facts and corporate activities, they are misleading and promotional, thus inappropriate.”[1] I whole heartedly agree but I would go a […]

Would like to join this awesome class!(^_^)